“I Would Prefer Not To”: The Rise of Refusal in Modern Relationships

Tuesday, January 13, 2026. This is for Sean and Kimberly.

Why People Are Done Explaining Themselves in Relationships

Before refusal had a name, it had a consequence.

Here’s our working definition: refusal, in a relational context, is the deliberate withdrawal from interpretive labor when explanation no longer produces care or change.

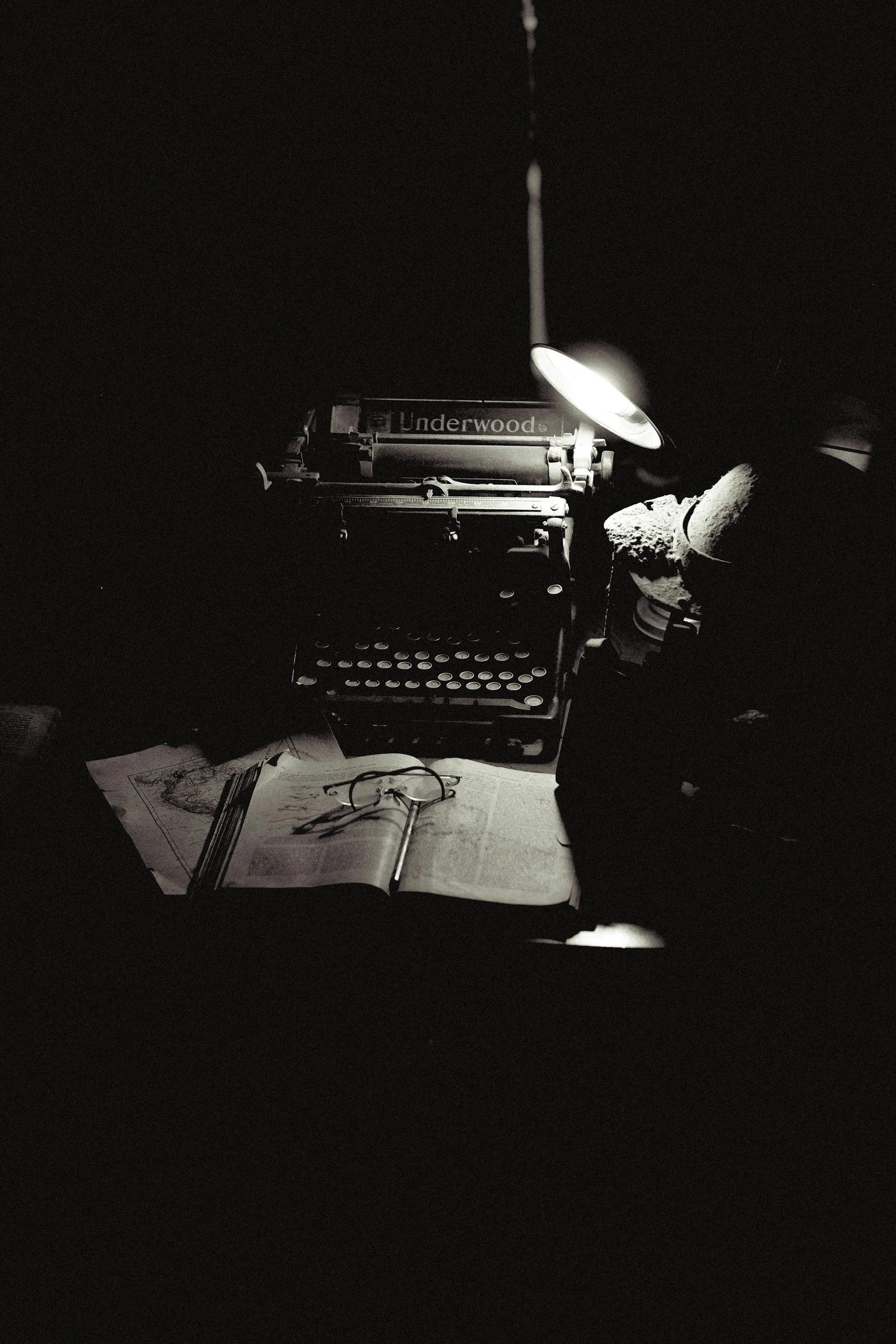

Bartleby, the Scrivener enters American literature in 1853 like a man who has already decided to stop explaining himself.

Herman Melville publishes the story in Putnam’s Monthly Magazine at a moment when America is drunk on progress, paperwork, and moral certainty.

Wall Street is still a narrow street, clerks copy documents by hand, and the virtue of the age is industrious compliance.

Into this comes Bartleby—quiet, polite, eerily functional—until he isn’t.

His innovation is linguistic, not dramatic. In Bartleby, the Scrivener, a quiet law clerk responds to every request—(copy this, review that, explain yourself), not with anger or defiance, but with a phrase so mild it destabilizes everyone around him:

“I would prefer not to.”

That sentence lands like a paper cut. No rage. No rebellion. No counter-argument. Just preference. And refusal.

The story is often misread as workplace satire or proto-existentialism, but historically it’s something sharper: a mid-19th-century crisis of conscience wrapped in office furniture.

Melville was writing after commercial failure, professional disappointment, and a growing suspicion that moral systems built on productivity were spiritually hollow.

Bartleby is not lazy; he is just done consenting.

Critics later claimed him.

Existentialists adopted him early. Kafka nodded. Camus took notes.

Modern burnout culture thinks he’s one of theirs. But in his own time, Bartleby was a scandal of passivity—proof that one could opt out without offering up a manifesto.

In short:

Bartleby is the first American character to discover that refusing to perform sincerity is more destabilizing than anger.

And that’s why he still unnerves people who run offices.

Bartleby does not argue.

He does not justify.

He does not clarify his inner world.

He simply withdraws consent.

What unsettles his employer is not the refusal itself, but the refusal’s calm indifference to explanation.

There is no misunderstanding to resolve. No leverage point.

Bartleby does not oppose the system.

He stops participating in it.

Something very similar is happening in intimate relationships right now.

What Refusal Is:

Refusal is the deliberate withdrawal from interpretive labor—the work of explaining, contextualizing, translating, softening, and justifying one’s inner life so another person can feel oriented, reassured, or morally settled.

A boundary still collaborates.

It explains the line and why it exists.

Refusal ends collaboration.

It says: I am no longer available for this exchange.

That distinction matters clinically—and culturally.

Why This Is Happening Now

Refusal is not a trend. It is a response.

It sits on top of three pressures that are well established in social science.

The concept of emotional labor was introduced by Arlie Russell Hochschild in The Managed Heart, demonstrating that managing emotions to meet social expectations is a form of labor with real psychological consequences—even outside paid work.

Later scholarship extended this into emotion work within private life: how people regulate feelings to sustain relationships and households.

In intimate relationships, this labor includes:

anticipating reactions.

managing tone.

explaining feelings “the right way.”

repairing misunderstandings repeatedly.

This effort is cognitively taxing. Over time, it accumulates cost.

Refusal emerges where the bill has gone unpaid for too long.

Emotional Labor Is Unevenly Distributed

Research and sociological reporting consistently show that emotional and cognitive labor falls disproportionately on women in heterosexual relationships—even in couples who describe themselves as egalitarian.

This includes:

initiating difficult conversations.

maintaining relational climate.

remembering emotional details.

translating conflict into “productive dialogue.”

Refusal rarely appears early.

It appears after years of over-functioning.

Like Bartleby, the refusing partner has usually already complied—extensively.

When “Just Communicate” Stops Working

For decades, modern relationships have been governed by a moral rule: If you are reasonable, you will explain yourself.

Therapy culture reinforced this. Emotional transparency became synonymous with care.

But research on chronic conflict and demand–withdraw patterns complicates the promise.

Increased articulation does not reliably produce behavioral change when motivation or capacity is mismatched.

In those cases, more explanation increases frustration rather than intimacy.

At that point, communication becomes extractive.

Refusal is not a failure of skill.

It is the exhaustion of hope that explanation still matters.

Refusal as a Response to Over-Access

Modern intimacy assumes near-total access to another person’s interior life.

Feelings must be named.

Motives clarified.

Reactions processed collaboratively.

Research on self-disclosure norms shows that expectations for openness are culturally shaped and historically variable, not universal..

Refusal is not silence.

It is a renegotiation of access.

It says: You no longer have unlimited interpretive rights to me.

Bartleby understood this long before we did.

Social Media Proof: The Language of Exhaustion

This shift is visible across platforms without coordination.

On Reddit relationship forums, posts describing being “done explaining” reliably receive thousands of affirming responses—especially from people describing long-term relational imbalance.

On Instagram, emotional burnout discourse increasingly frames explanation as labor, echoing psychological research on emotional exhaustion (example synthesis).

The language converges:

“I’ve said it every way I know how.”

“I’m not doing the work of making this make sense anymore.”

“I don’t owe a presentation.”

This is not impulsive withdrawal.

It is cumulative refusal.

The Quiet Quitting Parallel

The rise of quiet quitting at work—documented by Gallup and widely summarized —offers a precise parallel.

Quiet quitting is not disengagement from responsibility.

It is disengagement from unpaid surplus labor.

Refusal in relationships functions the same way.

People remain present.

They simply stop volunteering emotional overtime.

Bartleby kept showing up to the office, too.

Clinical Distinction: Refusal vs. Withdrawal

This distinction matters in the therapy room.

Withdrawal is fear-driven and often dysregulated.

Refusal is cost-driven and organized.

Withdrawal hopes to be reached.

Refusal has already decided the reach is no longer worth the price.

Treating refusal as avoidance misses its adaptive logic.

FAQ: Refusal in Relationships

Is refusal the same as stonewalling?

No. Stonewalling is typically a physiological shutdown linked to overwhelm. Refusal is deliberate. Stonewalling says I can’t do this. Refusal says I won’t keep doing this.

Is refusal emotionally unhealthy?

Not inherently. Research on emotional labor links chronic, unreciprocated emotion work to burnout and emotional exhaustion. Refusal often stabilizes what explanation can no longer repair.

Why does refusal feel so cruel to the other partner?

Because it removes narrative closure, moral reassurance, and the chance to repair through explanation. Modern intimacy equated explanation with love. Refusal violates expectations of access—not attachment.

Can a relationship recover after refusal?

Occasionally, but rarely without structural change. Repair requires reduced emotional labor asymmetry and observable behavioral shifts—not better explanations.

What should therapists listen for?

Long histories of “saying it every way possible,” emotional flatness rather than agitation, and clarity without bitterness. Refusal is often the final data point, not the presenting problem.

Final Thoughts

Bartleby never tells us why.

That is the point.

Refusal is not cruelty.

It is not immaturity.

It is not anti-intimacy.

It is what emerges when emotional labor becomes visible—and unsustainable.

Not everything needs to be processed.

Not everyone gets closure.

And sometimes the most honest sentence left in a relationship is the quietest one:

I would prefer not to.

Be Well, Stay Kind, and Godspeed.

REFERENCES:

Beach, S. R. H., Fincham, F. D., Katz, J., & Bradbury, T. N. (2003). Social support, marital satisfaction, and depression: The role of self-disclosure. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(1), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.94

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press.

Hochschild, A. R. (2003). The commercialization of intimate life: Notes from home and work. University of California Press.

Overall, N. C., & Simpson, J. A. (2015). Attachment and dyadic regulation processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.008

Sun, J., Schwartz, H. A., Son, Y., Kern, M. L., & Vazire, S. (2023). Cultural variation in self-disclosure on social media. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.15197