The Politics of “Please Don’t Hurt Me”

Tuesday, February 10, 2026.

We like to believe our political beliefs are principled.

That we reason our way into them.

That we compare arguments, weigh evidence, and arrive—earnestly—at a moral position.

Recent psychological research suggests something less flattering and far more useful.

Much of our political thinking appears to be organized around a simpler question:

Who might hurt me—and what would it cost to keep them from doing so?

Not rhetorically.

Not emotionally.

Physically. Socially. Economically.

The kinds of harm human beings have always organized themselves to avoid.

Redistribution as Risk Management

One implication of this research is quietly destabilizing:

redistribution may function less like generosity and more like appeasement.

Not:

“This is just.”

But:

“This is safer.”

Not:

“Everyone deserves the same.”

But:

“Extreme disparity invites consequences.”

In this framing, redistribution becomes a form of conflict insurance—a way to reduce the likelihood of revolt, destabilization, or violence by narrowing visible gaps before they provoke action.

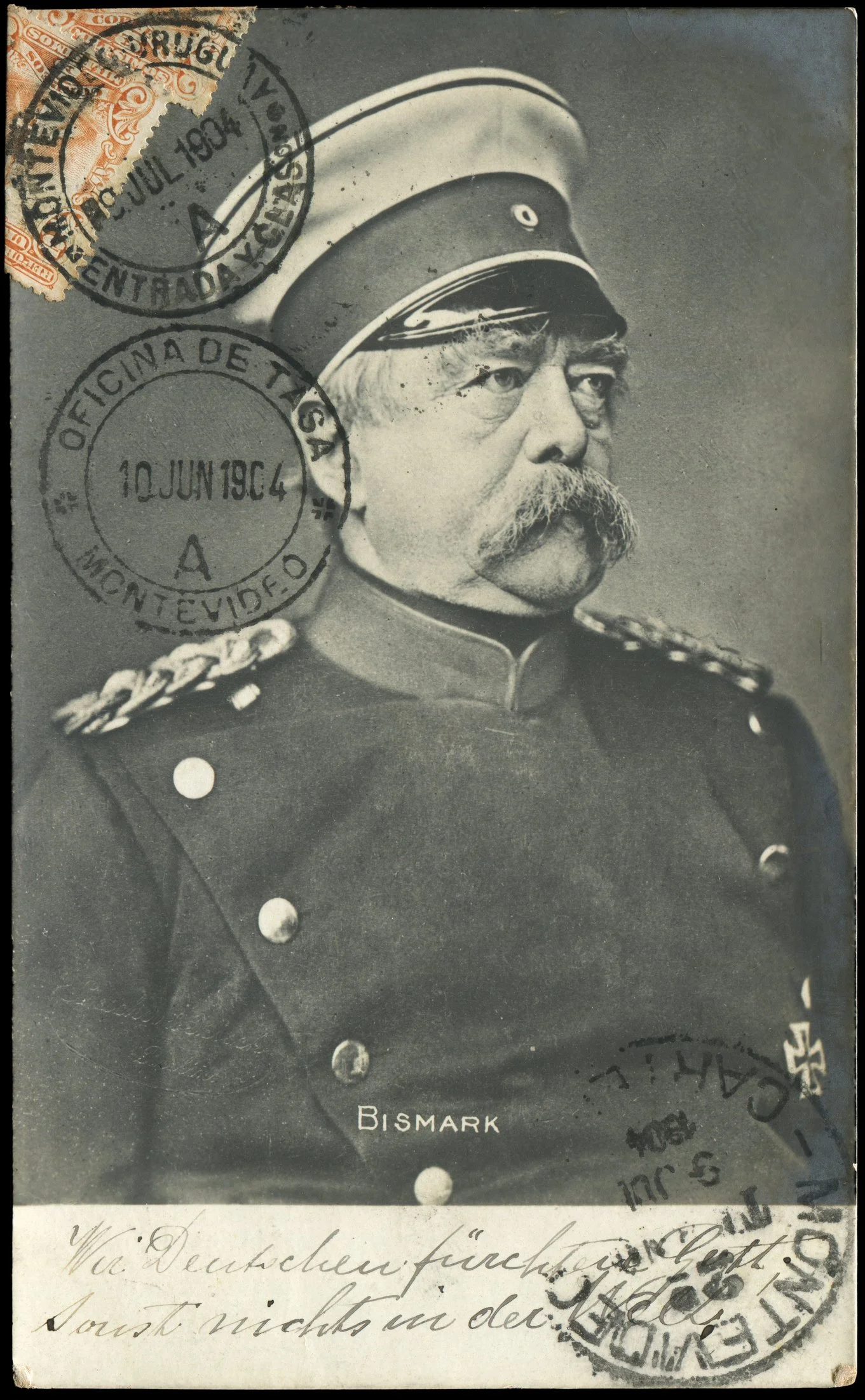

Otto von Bismarck understood this perfectly. He did not build the welfare state because he trusted human goodness. He built it because he distrusted desperation.

The poor were not a moral problem.

They were a volatility problem.

Egalitarianism Is Not Niceness

One of the more bracing findings in this body of work is that egalitarianism is not primarily about kindness.

It is about equalizing outcomes so no one feels compelled to flip the table.

The underlying logic is not:

“I want everyone to flourish.”

It is:

“I want no one desperate enough to come for me.”

That isn’t cruelty.

It’s evolutionary bookkeeping.

Groups that tolerated runaway inequality did not fail gracefully.

They failed violently.

From this perspective, egalitarian fairness is not moral idealism.

It is preventative maintenance.

Why Coercion Keeps Appearing

Once fairness is defined strictly by outcomes, enforcement becomes inevitable.

If redistribution is functioning as a threat-reduction strategy, then resistance stops looking like disagreement and starts looking like risk introduction.

And when fear organizes a system, coercion stops appearing immoral and begins to look efficient.

This helps explain a counterintuitive finding in the research: compassion does not reliably reduce support for coercive measures once fear enters the picture.

Compassion asks, How do we help?

Fear asks, How do we stop this from escalating?

Different motives.

Different ethics.

Progressive Policy as Appeasement Language

This same logic extends beyond taxation.

Policies as varied as redistribution, quotas, DEI mandates, and symbolic power transfers often travel together—not because they are intellectually unified, but because they are emotionally coordinated.

Each one signals, in a different register:

We are yielding. Please don’t escalate.

That isn’t hypocrisy.

It’s strategy.

Appeasement, after all, is not a failure of intelligence.

It is what systems do when they perceive danger and lack a better option.

Why Appeasement Eventually Fails

Appeasement stabilizes systems in the short term.

It rarely resolves the imbalance that made appeasement necessary.

Over time, concessions become expectations.

Risk thresholds recalibrate.

New demands emerge.

Appeasement lowers immediate threat but leaves underlying power relations intact—and unresolved systems do not remain static. They either renegotiate authority or revisit conflict.

This is as true in politics as it is in intimate relationships.

Anyone who works with couples has seen the pattern: one partner yields resources, autonomy, or authority not because they agree, but because they are managing danger.

It works—until it doesn’t.

Eventually, the bill comes due.

FAQ: What the Research Shows (and What It Doesn’t)

Is this saying people support redistribution because they are selfish or cowardly?

No. The research identifies multiple evolved motives operating simultaneously, including compassion, self-interest, envy, and fear. Fear is not a character flaw; it is an ancient strategy for avoiding harm.

Does this mean compassion doesn’t matter?

No. Compassion predicts support for redistribution. What it does not reliably predict is resistance to coercion once fear and instrumental harm are present.

Is fear of violent dispossession just general anxiety?

No. It is a specific fear related to loss of resources through force or social breakdown, and it predicts political views even when controlling for ideology, party affiliation, and general anxiety.

Does this research prove fear causes political beliefs?

No. The findings are correlational, not causal. They identify robust, replicated associations and outline plausible evolutionary mechanisms that require further experimental testing.

Why does appeasement fail?

Because appeasement reduces immediate danger without renegotiating power. Over time, unresolved asymmetries resurface. This is a systems problem, not a moral one.

The Uncomfortable Recognition

This research does not tell us which policies are right.

It tells us something more unsettling:

Much of our political morality may be built on fear rather than virtue.

Once you see that, debates framed purely as good versus evil begin to feel strangely thin.

Because beneath them runs an older conversation—one we rarely admit we are having:

Who has what.

Who might take it.

And what it would cost to stop them.

That conversation predates democracy.

We have simply learned to drape it in moral language.

Be Well, Stay Kind, and Godspeed.

REFERENCES:

Lin, C.-A., & Bates, T. C. (2024). Support for redistribution is shaped by motives of egalitarian division and coercive redistribution. Personality and Individual Differences.